Oceanographers have finally found an explanation for the existence of a large area of cold water in the Atlantic Ocean, south of Greenland.

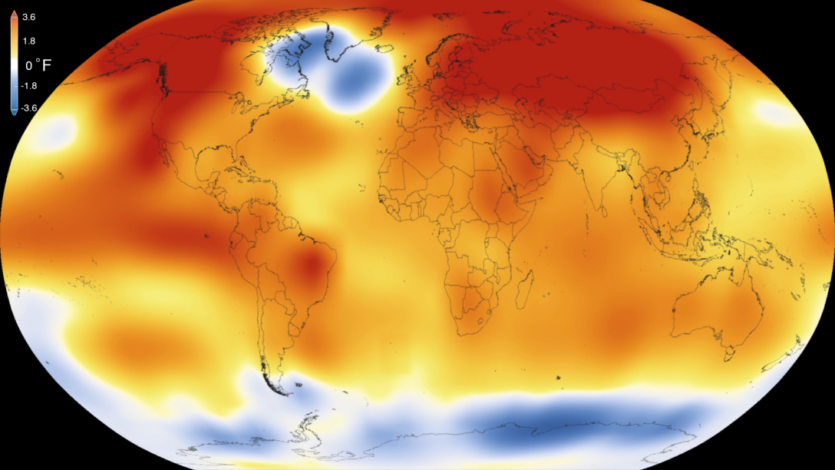

Contrary to logic, this anomalously cold area in the Atlantic Ocean is called the North Atlantic Warming Hole. Despite the fact that around the world ocean temperatures are rising, in this region, the temperature has fallen by 0.3 C° over the past 100 years.

Based on the results of the analysis of ocean temperature and salinity, scientists have linked the decrease in temperature in this zone to a slowdown in the ocean current system called the The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), which carries cold deep waters southward and warm surface waters — northward. The cold region has long been a source of debate among oceanographers. Some attributed its existence to ocean dynamics, while others considered it to be one of the consequences of atmospheric pollution by aerosols.

The scientists have now confirmed that the anomalously cold area is influenced by ocean dynamics. Since direct observation of the ocean current system has been conducted only for the last 20 years, scientists have used the data to monitor an earlier dynamics of ocean currents. They used temperature and salinity data that correlate with current current speeds to uncover AMOC patterns from the past century, and used 94 different ocean models to assess changes.

Having a clear scale of dynamics AMOC over time, the researchers found that only models that included a slowdown in ocean currents were associated with real cooling. The researchers emphasize, that a better understanding of how the AMOC is slowing down not only explains the cold stream but also contributes to climate forecasting. The AMOC and the anomaly it creates affect European weather patterns, including precipitation and wind.

Marine ecosystems can also suffer from changes in currents as water temperature and salinity can determine the local habitat of some species. In addition, scientists are concerned that the AMOC will slow down by at least 20% by 2100, but it is unclear whether the ocean current system will stop completely.

The results of the study are published in the journal Communications Earth and Environment

Source: LiveScience

Spelling error report

The following text will be sent to our editors: