Research by an American scientist Luis Amaral of University of Northwestern indicates the existence of a wide international network of science fraudsters.

Amaral notes, that scientific fraud is no longer a matter of a few. It is not a matter of unscrupulous individuals, but an organized system that is developing more rapidly than real science. It includes wide networks of editors and authors who cooperate to publish pseudo-research in large volumes.

They use system vulnerabilities for laundering reputations, obtaining funding, and raising their own academic ratings. We are talking about a large and stable system, that in some cases imitates organized crime

“These networks are actually criminal organizations. Millions of dollars are involved in these processes”, — Amaral explains.

Research Luis Amaral’s study is based on the analysis of more than 5 million scientific articles from more than 70 thousand scientific journals. The researchers also studied tens of thousands of refutations, magazine editorials, and even copies of images.

This allowed the researchers to identify a fraudulent scheme — “paper mills” that churn out low-quality research. Intermediaries, who sell authorship and the opportunity to publish in scientific journals. Unscrupulous editors, who are ready to automatically approve fake research.

One of these “paper mills” is indicated as Academic Research and Development Association (ARDA). Between 2018 and 2024, ARDA expanded its list of affiliated journals from 14 to 86, many of which were indexed in major academic databases.

As a result, some of these journals turned out to be fraudulent. Their activities were illegally resumed after the original publishers stopped publishing. Luis Amaral argues, that the materials, offered by ARDA and similar organizations, are not science. Clients pay to have their names listed in pre-prepared papers, often without any real research to improve their resume, which later leads to material benefits.

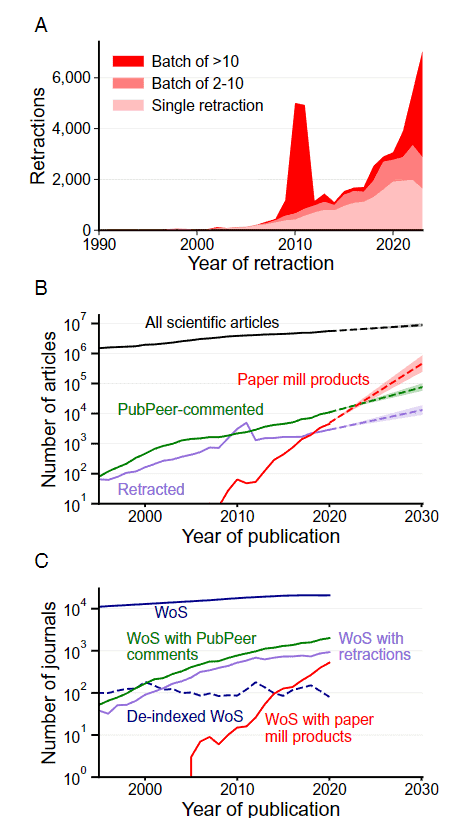

According to the authors of the study, “paper mills” now double their production every 1.5 years. At the same time, the number of refutations — the main corrective measure of the scientific community — doubles every 3.5 years.

The results of the study show that even some respected scientific publications have been influenced by science fraudsters. The researchers determined that. A very small group of editors – less than 0.3% in one journal — was responsible for about 30% of all retracted articles. These editors were not engaged in fraud detection, but rather indulged him.

“You either believe in scientific fraud or you leave science. Tens of thousands of scientists have found themselves in this situation”, — said Reece Richardson, the study’s lead author and a sociologist at Northwestern University.

The analysis showed that they often accepted each other’s articles, bypassing proper peer review and creating a vicious cycle of mutual approval. One particularly active group in PLOS ONE was active from 2020 to 2023, and many of the accepted articles were subsequently withdrawn for similar reasons. Similar cases were found in Hindi language magazines and even in the proceedings of IEEE conferences.

To detect fraud, a team of researchers, led by Richardson’s, drew attention to things like the reuse of images, which indicated copying and repackaging research data In one network, only a third of the 2,213 articles with duplicate images were withdrawn.

Other signs of fraud include an expedited review process that takes less than 30 days, unusual spikes in publications in certain journals and unnatural patterns of authorship — for example, co-authors with no family ties to the rest of the world in highly specialized technical articles.

Many of these pseudo-studies are related to specific subfields, in particular, microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs in cancer biology. The more specialized and little-known the study, the better, as it adds another layer of opacity. In these sub-areas, recall rates reached 4% compared to 0.1% in more established areas such as CRISPR.

Fraudulent research misleads real scientists, distorts the results of meta-analyses, wastes public funds, and undermines real research. The authors examined the case of Alzheimer’s disease research.

Just one pseudoscientific article attracted billions of investment funds and forced scientists to spend years on unpromising research, before it was discovered, that the original study was fraudulent. During the COVID-19 pandemic, fraudulent research contributed to the use of hydroxychloroquine, which indirectly led to 17,000 deaths.

The career of scientists is based on the number of publications. The more articles a researcher publishes and the more they are cited, the more funding and research staff they will receive, and the more prestige they will gain. In a hyper-competitive system with limited resources, incentives tend to favor quantity over quality.

According to the authors of the study, the existing tools to counteract science fraudsters, such as retracting pseudoscientific articles and revoking journals’ licenses, are insufficient. Some fake articles remain in the databases even after the relevant journals are de-indexed. Others continue to be cited, creating a stream of disinformation.

Richardson and Amaral advocate for deeper systemic changes: separating tasks that provoke conflicts of interest, such as peer review, from the business interests of journals, rethinking academic incentives, and moving away from simplistic indicators such as the number of citations or the journal’s impact factor.

The situation is further complicated by rapid development of generative artificial intelligence. If AI models are trained on questionable data, their effectiveness in new research can be questioned from the start.

In addition, there is the problem of scientific articles created with the help of AI. In 2024, a peer-reviewed scientific journal published a study with an obviously AI-generated chart that depicts a cartoon rat with a giant penis. The article was retracted only after the image went viral on social media.

“We have no idea, what will end up in the literature, what will be considered scientific fact and used to train future AI models”, — warns Reece Richardson.

Some academic publishers, such as Springer Nature and Frontiers Media, are beginning to retract articles en masse. Recently, Frontiers retracted 122 studies after finding evidence of citation manipulation and hidden collusion among reviewers. But these efforts are only superficial. Richardson estimates, that only 15-25% of fake articles will be retracted.

According to the authors of the study, to change the situation, it is necessary to change the culture. Funding organizations should reconsider their methods of evaluating successful scientific materials. Journals should invest in independent integrity checks. And researchers should be supported in choosing quality over quantity. Without reforms, future discoveries — and the public good they are intended to serve — may be built on sand.

The results of the study were published in the journal PNAS

Source: ZME Science

Spelling error report

The following text will be sent to our editors: